views

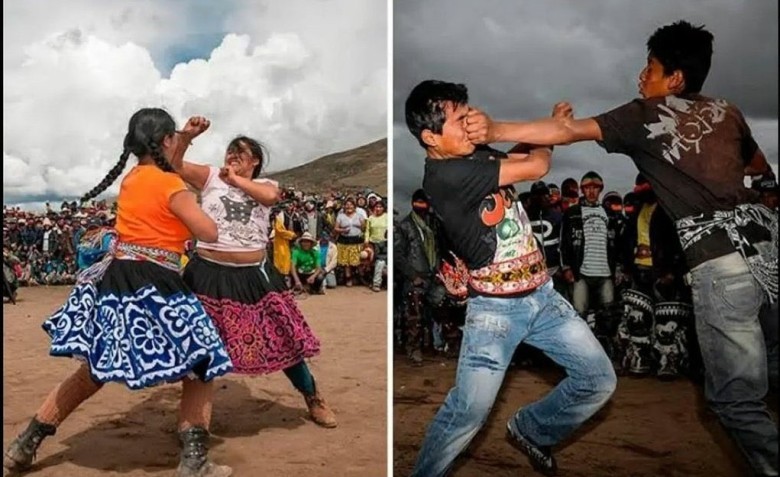

Every December 25th, as much of the world unwraps gifts and gathers for festive meals, a remote corner of Peru ignites with a tradition unlike any other: Takanakuy. Hidden in the high-altitude provinces of Chumbivilcas, this extraordinary annual festival is a raw, visceral, yet deeply communal ritual where men, women, and even children settle their grudges with bare-knuckle fistfights. And once the dust settles and the last punch is thrown, everyone goes drinking together, ready to embrace the new year with a truly clean slate.

The name "Takanakuy" itself, derived from Quechua, roughly translates to "to strike each other." Far from chaotic brawling, this is a highly ritualized event, steeped in tradition and governed by strict rules. Participants, often adorned in vibrant, traditional costumes—some wearing ski masks, others animal-themed headwear—enter a designated ring. Before each bout, a referee, often a local authority figure, ensures that both parties agree to the fight and that no weapons are involved. The combatants, who might be neighbors, relatives, or former friends, engage in a brief, intense exchange of blows, typically lasting only a few minutes. Kicking, hair-pulling, and hitting someone when they're down are strictly forbidden, and the fight ends when one person falls, or the referee deems it over.

The purpose of Takanakuy is not simply violence, but catharsis and reconciliation. It's a structured mechanism for airing grievances and resolving disputes that have festered throughout the year—be it over land, livestock, personal insults, or family squabbles. By confronting their adversaries directly, physically, and publicly, participants believe they can purge negative emotions and prevent lingering resentments from poisoning the new year. The pain of the punches is seen as a necessary part of the process, a physical manifestation of the emotional release.

Once a fight concludes, regardless of who "wins" or "loses," the combatants are expected to shake hands, embrace, and often share a drink. This act of immediate reconciliation is crucial. The grudges are settled, the slate is wiped clean, and the community can move forward in harmony. The day then transitions into a grand communal celebration, with music, dancing, and copious amounts of chicha (a traditional corn beer), reinforcing bonds and collective identity.

Takanakuy is a powerful testament to the ingenuity of human communities in devising unique methods of maintaining social order and fostering cohesion. It's a fascinating glimpse into a cultural practice that, while jarring to outsiders, serves a vital function within its context: a raw, honest, and ultimately unifying way to confront conflict, forgive, and ensure that the new year begins with a spirit of renewed peace and collective well-being.

Comments

0 comment